Xenogears: How Ambition and Heart Outshine Compromise

A first-time director making something unlike anything that Squaresoft had put out before, a development team mostly made up of junior developers, and a two-year deadline that cut off the game’s development timeline. In spite of the circumstances of its development, Xenogears still stands as one of the most ambitious video games ever created. // Image: Square Enix

Charm is elusive. It is an essence that you cannot intend to capture when beginning a project. Charm is never an intentional tone that gets naturally elicited from the author to the audience. Rather, charm is something that the audience feels when there’s something special about a text - when there’s an unmistakable feeling that a project is punching above its weight and trying to reach for the stars despite being ostensibly grounded.

In the modern video game landscape, big-budget projects have become so risk-averse for the sake of securing millions of sales and coveted green Metacritic scores that they fail to be strange, ambitious, and different. Charm is something that we currently primarily see from games produced by indie developers and publishers, all of whom have significantly less resources to work with than your average AAA game developer. The lack of such resources causes many independent developers and publishers to get creative with how they integrate ideas into their projects, how certain game mechanics are developed, and how these games are marketed to audiences. The lack of resources, money, and time cause human creativity to make up the difference - and that, I feel, is what creates charm and whimsy to an experience. The necessity of the human spirit to make a project see the light of day is what leads to indescribable charm.

Earlier this year, I completed a full playthrough of Xenogears for the first time. As the credits rolled and I started thinking about how I could meaningfully reflect on my experience playing the game for a blog post, a few words popped into my head - the most prominent one being: charming.

Xenogears is charming, and a lot of that is due to the fact that it is a game that should not exist.

It is impossible to discuss Xenogears without mentioning the severely troubled environment in which it was developed and the compromised state that it ended up releasing in. Initially written after Final Fantasy VI and pitched as a potential candidate for Final Fantasy VII after development on Chrono Trigger wrapped, Tetsuya Takahashi’s vision was ultimately allowed to be developed as a new IP. After two years of development, this new IP would release in 1998 as Xenogears in the midst of Squaresoft’s golden era during the reign of the original PlayStation. Although the game was developed during a period of great success for the Japanese publisher, Xenogears’ success was never assured.

Squaresoft’s general policy at the time was to put games on a strict two-year timeline for their development. This policy gave a hard deadline on Xenogears’ completion, leading to various compromises made for the final product to ship, including but not limited to the game’s infamous second disc that abridges the second half of the game’s story. In addition to a limited development timeline was a lack of experience. Xenogears was Tetsuya Takahashi’s first time in the director’s chair for a game. Likewise, much of Xenogears’ staff consisted of junior developers that were still getting accustomed to the complex nature of developing 3D games.

In spite of all of these limitations put onto the game’s development, Takahashi remained undeterred in creating something unprecedently big, ambitious, and intelligent. Xenogears was written by Tetsuya Takahashi and Kaori Tanaka (also known by her pen name, Soraya Saga) with the intention of being a marriage of two narrative aspirations between the two authors. Takahashi wanted to write a story about an assassin with amnesia while Tanaka sought to create a narrative about a woman that gives birth to a new race of humans. The story they would write together would merge these two concepts into one behemoth story that would take place over thousands of years. As would be revealed by the game’s final screen and the eventual release of its companion book, Xenogears: Perfect Works, the game Xenogears is, in actuality, the fifth part of a far larger story.

While previous episodes of the original vision of Xenogears are teased in flashbacks throughout the game, the vast majority of the original story that was planned never materialized. What was drafted as a story that tackled concepts of religion, control, abuse, mental illness, Gnosticism, the myth of creation, psychology, Nietzschean philosophy, perpetual war, and so much more was ultimately too ambitious for its own good. Xenogears didn’t reach its full potential because it simply couldn’t in the environment, industry, and point in time in which it was conceived. Xenogears couldn’t succeed and become the IP it was envisioned as, in part, due to circumstances outside of its creators’ control.

Xenogears never fully lived up to its original creative vision for a lot of reasons, but it can’t be argued that Xenogears tries to do something no other games have done before or since. Very few games intellectually engage with real-world psychology, philosophy, and religion with such criticism, earnest curiosity, and complexity in the way that Xenogears does. Very few games, especially circa the late ‘90s, dare to have lore, worldbuilding, and conflict nearly as deep and far-reaching as Xenogears out of fear of making a narrative that goes over the heads of many players. And yet, Xenogears just goes for it anyway. It tackles so many subjects and tells a complex, meaningful story depicting tragedy, love, hope, and self-reflection - all while asking what it means to become whole. That’s a lot for any story to tackle - to say nothing of a story for a video game with the limited technology of the original PlayStation to tackle.

For a game as broad, ambitious, and nuanced as this game is with all of its subject matter and depth to not have the time and development resources to realize its ambition, how could this game succeed? Was there ever truly a universe where Xenogears would have been able to realize what was originally envisioned?

We’ll never know the answers to those questions. All we can know is the game that, despite the odds stacked against it, ended up shipping and became a finished product - one that got an English localization, no less! Xenogears is a deeply flawed game that reeks of compromise throughout the entire experience.

Despite all its issues and imperfections, though, Xenogears is a game that is impossible to forget. No matter what, you will always remember the wild directions that Xenogears’ plot goes in. You will always remember the way it engages with certain ideas and themes. You will always remember the late-game reveals that paint the full picture of Fei and Elly’s relationship with each other. There are so many moments in Xenogears that touch the player’s soul in ways that few games or other pieces of media ever even attempt to do.

Xenogears’ strengths as a video game are all in spite of the barriers and obstacles that got in the way of it realizing its true potential. Although it isn’t the best game that it could have been, Xenogears still manages to feel special and meaningful to play nearly thirty years after its release. To me, such a thing is inspiring, monumental, and, well, charming.

Xenogears punches above its weight and tries to be something that few video games have ever dared to be: an opportunity to ask remarkably human questions. Maybe it can be argued that some of its ideas don’t land, are rushed, don’t translate properly in the game’s localization, or feel convoluted - but Xenogears tries. Xenogears is a game that tries despite it all, and that’s what has kept me thinking about it ever since I rolled credits.

Underlying any effort to tell a meaningful story is a deeply admirable goal: to offer a piece of yourself into the world. The story that Takahashi and Tanaka crafted in Xenogears is intrinsically a part of themselves - their intellectual ideas, personal curiosities, and perspectives on the nature of humankind wrapped into a playable piece of media. Put another way, Xenogears was made with heart alongside its ambition. The game’s developers part all of themselves into the game, and the fruits of that make a game that feels inherently special. Such a thing creates an infectious charm that envelops the game.

Past all of its high-concept ideas, science-fiction terminology, and RPG systems, Xenogears is a deeply human game that’s impossible to not admire at the very least. Let’s talk about how Xenogears’ ambition and heart cut through the noise of the game’s compromised state in order to make an unforgettable narrative that game developers and writers alike can still learn lessons from over a quarter century after its original release.

Xenogears’ cast is yet another reminder of its compromised state. While Fei, Elly, Citan, and Bart are essential contributors to the game’s narrative, characters like Rico, Maria, Billy, and Chu-Chu get severely understated presences in the game’s story that only sees them be relevant for an arc or two. // Image: Square Enix

I’ve always felt that the very best narratives in games are the ones that start small and gradually ramp up stakes. Final Fantasy IX, one of my personal favorite games of all time, creates great narrative tension thanks to the strong juxtaposition in its tones. That game’s adventure brings its characters together in a way that invites fun, humor, and a light-hearted spirit of adventure that starts off brightly, before gradually unraveling a darker, more philosophical narrative that tests the characters we connect with.

The juxtaposition between brightness and darkness in a game’s narrative helps diversify the game’s tone as well as creating an environment where players can get comfortable with the game’s characters and setting before testing and challenging that comfort with hardships that test the characters and the state of the world they live in.

Xenogears opens in a very similar way, with a great bit of mystery and intense worldbuilding thrown in for good measure. Upon starting Xenogears, the player is treated to a marvelous anime cutscene that is as intriguing as it is harrowing to watch. A spacecraft self-destructs upon a threat being discovered, leaving a purple-haired woman waking up amidst the wreckage as she looks out to a seemingly untamed planet in the distance. This opening immediately begets various questions - ones that won’t be answered for the player for the majority of the game’s runtime. This sets an expectation for the player throughout Xenogears: the game will plant big, mysterious narrative seeds that the player won’t see the fruits of for some time. But when those narrative seeds eventually bear fruit, they lead to incredible payoffs.

After the anime opening, Xenogears opens with a text crawl going over the primary conflict that contextualizes the game’s initial setting. Two countries have been locked in a 500-year-long war and have forgotten the very purpose of the war for some time. Kislev and Aveh’s perpetual war with one another have made violence and fighting a fact of life for the citizens of this world. Ethos, referred to as the Church in the original Japanese script, is a third-party entity that excavates ancient technology that both countries use in their warfare.

After this text crawl, we zoom in on Lahan Village, a quaint, countryside town that’s in crisis. Buildings are burning, townspeople are dying, and two giant mechs are fighting against each other. The chaos of war overtakes this village until we zoom out and reveal Fei is painting in his home. It’s here, after two introductory scenes that start with action and a noun-filled text crawl, that we finally begin the game in a grounded setting. Lahan Village is a peaceful home-like starting point for the adventure. There is a solid hour’s worth of content just to navigate through the village and talk to the various NPC villagers.

This cozy quietude offers the first glimpse of brightness in this narrative - which heavily contrasts the two dark scenes that play at the game’s onset. It’s through this brightness that the player falls into a comfort in familiarizing themselves with Fei, Lahan Village, and the many characters that inhabit this world. While still taking opportunities to plant narrative seeds, such as the mysterious man that brought Fei to Lahan Village three years ago and the fact that Fei doesn’t remember anything from before he lived in Lahan, this opening area of the game grants brightness into this world. The music and overall vibe of Lahan Village has a familiar warmth. There’s a scene between Fei and his friend, Alice who is getting married to Fei’s other friend, Timothy. During this scene, there’s an implication of a potential romance between Fei and Alice that’s tragically never meant to be, primarily due to circumstance.

This thread ultimately gets cut short not much longer into the game, but its presence is very much appreciated and justified because it grounds Fei’s presence in this slice of the game’s world. Fei may not remember his life before Lahan Village, and he doesn’t get the opportunity to marry Alice because he didn’t meet her when they were younger, but he has nevertheless found a community. A found family, if you will. Fei has found a home - and this homeliness is the very cozy essence that encapsulates the tone of this early segment of the game.

The brightness allows the player to become attached to Fei and the denizens of Lahan Village in a short time, even in the face of so much mystery outside of the village. Upon meeting and spending time with Citan, the village’s doctor, tragedy strikes Lahan Village. Fei rushes to the village to see that Gears involved in the war between Kislev and Aveh have wrought destruction upon the village. Fei begins commandeering one of the Gears, contextualizing the first scene we saw take place in Lahan. After a combat encounter and introduction of Gear combat, Fei’s memory goes blank. The following morning, Fei discovers that the village has been destroyed and many of its inhabitants, including Alice and Timothy, are dead. What’s more - Fei is responsible for this death and destruction. He gets swiftly banished from the village by the remaining survivors.

And just like that, darkness has overtaken the brightness, warmth, and comfort that the player was once enveloped in. Brightness gave us an opportunity to get familiar with this world. The juxtaposing darkness forces the player to accept the harsh realities and cruelties of this game’s world and informs us of the direction that Xenogears is willing to go.

Upon meeting Elly in the nearby Blackmoon Forest, Fei practically asks Elly to kill him, believing that he has nothing left to live for. Not long after, Fei finds himself questioning the meaning of fighting in the world, unsure of whether it’s worth struggling in the world to fight for something. Despite these questions, Fei regroups with Citan, and ventures through the world to find a way forward.

I have recounted the beginning of Xenogears’ narrative because I feel that it does a phenomenal job at setting the tone of the entire experience. Xenogears’ story is one wrought with tragic hardship and isn’t afraid to challenge its characters. The juxtaposition between the warmth the player feels during Xenogears’ opening section and the ensuing dark depths that the game is willing to go to meaningfully illustrates the ambition inherent to Xenogears’ mission.

Through smart worldbuilding, long stretches of cutscenes that take their time in establishing and developing character relationships, and big, bombastic payoffs to narrative setups, Xenogears regularly has exciting and well-crafted story sequences that regularly impress. The game regularly utilizes instances of levity and brightness to set up a narrative thread, then be unafraid to take a dark turn in order to create meaningful narrative payoff.

Xenogears is a game mostly compromised of arcs, creating a kind of rhythm to the game’s narrative throughout the first disc. For example, the next arc sees Fei traveling to Aveh to information about the nature of the attack that occurred at Lahan Village. This takes Fei and Citan to Dazil, a desert village that returns the game to a cozy, bright opportunity to get enveloped in the game’s characters, world, and attention to detail. Throughout this arc, we see glimpses of mystery and darkness, such as when Fei encounters Grahf for the first time, before the bright, witty nature of Fei and Bart’s relationship bring the conflict back down to Earth. This arc in Xenogears culminates in a siege on Aveh’s capital, mixed with a tournament that sees Fei confront Dan, one of the survivors from Lahan who’s brimming with grief and resentment towards Fei. There’s a lot that happens in Xenogears, but because of the game’s commitment to having long cutscenes where characters reveal their intentions, plans, and revelations, major plot moments rarely feel underdeveloped in Xenogears.

All of the game’s arcs in the first disc follow this general template: Fei travels to a new part of the world, confronts new threats, finds new allies, mysteries are revealed and developed to the player, and a payoff to one of those mysteries propels the plot into a new direction that takes Fei and his party to another part of the world. This description makes the game sound more formulaic than it actually is, and that’s largely in part to how different each of these arcs feel from one another.

For example, one of the game’s arcs sees Fei imprisoned in Nortune, a massive, industrialized city that contrasts with the naturalistic architecture of all cities that the player has seen up to this point. This arc effectively serves as the “prison break” trope that JRPGs regularly like to depict, but the details, visuals, mysteries, and unique encounters of this section make the Nortune arc feel distinct from anything else in the game. There’s even a fairly in-depth fighting minigame that never reappears in the game (save for optional fights that the player gains access to later on). All this is to say that Xenogears takes what could have made for a repetitive, formulaic structure, and leans on its diverse scenarios, environments, and characters to make for narrative moments that feel regularly distinct and meaningful.

The arc in Nortune feels nothing like the arc in Shevat because the two environments feature entirely different visuals, music, encounters, dungeons, and characters that feel connected enough to believe that they’re part of the same world, but disconnected enough to convince the audience of the variety and detail of the various cultures in the world of Xenogears.

Xenogears admittedly features nowhere as many locations on its world map compared to just about every other JRPG made during Squaresoft’s golden era. Xenogears goes for quality over quantity in its locations, though, and the resulting settings and scenarios that take place within them lead to a story and world that feels consistently dynamic.

This is in line with the natural rate at which the game’s story elevates in scale and stakes. What starts as a seemingly straightforward story about Fei effectively having to start his life over gradually sees more narrative layers piling on top of each other to create a narrative as deep as it is interconnected. Xenogears does what every great narrative ought to strive to do, in that it builds mystery and solves those mysteries with revelations that invite more mystery and truths to be uncovered. The truth behind the conflict between Kislev and Aveh is revealed to the player, but that truth only invites further questions that beget the player to start asking different questions. The mystery behind Kislev and Aveh morphs into the history of and the relationship between Solaris and the land dwellers (or “Lambs”), which itself morphs into even more questions in time.

The mysteries in Xenogears are only as effective as they are because their respective payoffs keep the game’s narrative moving forward. As these payoffs are revealed, the true nature of Xenogears’ millennium-spanning timeline becomes apparent, which only invites further intrigue from the player. The ambition of such a long-spanning, complex story works ultimately works here because of the game’s digestible structure and the consistent injection of brightness amidst the game’s world and characters that keep the out-there concepts revealed later in the plot still feel cohesive. Xenogears’ ambition remains in check because it ensures itself to never go off the rails - and that, I feel, is the result of carefully detailed and well-paced writing.

All this is to say that the story is the main driving force that compels the player to explore the game’s environments, talk to its NPCs, navigate its dungeons, and engage with its combat system. While Xenogears does a lot as a video game, it’s very clear that the story is intended as the primary reason to play this game. And indeed, Xenogears is a game that’s very much worth playing because of its story and ambitious ideas, but that does unfortunately mean that the game isn’t as remarkable from a gameplay perspective.

On-foot combat in Xenogears utilizes amazing 2D sprites for characters and monsters. When in Gear combat, however, all party members and enemies are rendered in 3D, making Gear combat have a tangibly larger scale. // Image: Square Enix

Characteristic of Square’s general mission statement around the time of its release, Xenogears takes an opportunity to experiment with the turn-based battle format. While other JRPGs around this time period played with the genre formula by introducing classes, stat modifiers, and other means of making character progression feel more dynamic and customizable, Xenogears generally treads a different path. Xenogears’ main gameplay hook is that it features two battle systems - one that takes place on-foot and one that sees each party member pilot a Gear and gain access to a different moveset.

On-foot combat is the more conventional style of turn-based battles that genre veterans will immediately find themselves familiar with. Characters’ turns are represented by a bar that gradually fills up not unlike Final Fantasy’s ATB system, and the player can attack, cast spells, and use items during their turn. While this is all fairly standard, the injection of creativity and experimentation in Xenogears’ gameplay comes in the form of the Deathblow system. Instead of having a basic attack command, Xenogears has each of its characters to walk up to the enemy in question and perform a sequence of light, medium, and heavy attacks based on the player’s input. Doing different combinations of different types of attacks will gradually unlock Deathblows - combos that become the primary means of dealing damage in Xenogears.

Deathblows are everything they need to be: strong, flashy, and showing off some of the best audio and animation in the entire game. However, the Deathblow system’s greatest weaknesses come into view very quickly: you’ll be seeing a lot of the same animations again and again as you perform the same Deathblows in the game’s many battles. As characters level up, they’ll be able to perform more attacks per turn, unlocking stronger Deathblow combinations - but these aren’t handed to the player. Rather, the player has to perform the same sequence of attacks multiple times in order to learn the Deathblow associated with that particular sequence of button presses.

This leads to a conflict for the player: do you grind out doing every button combination to learn every Deathblow, but sacrifice your damage output while doing so? Or do you just take the Deathblows you naturally get during your playthrough and don’t reap the rewards of having more Deathblows? This system is oddly one of Xenogears’ only real instance of grinding. Due to the game’s decisively linear nature, the difficulty of encounters never sees the substantial spikes or hurdles you’d typically see in other JRPGs. Xenogears isn’t necessarily easy - rather, it’s a game where the player doesn’t have many options at their disposal. That lack of options means that players simply have to optimize the use of their limited pool of tools during combat. Encounters throughout Xenogears can only be so difficult when the player can only consider its relatively small quantity of mechanics during its tougher battles.

The saving grace of investing in learning Deathblows is that they carry over to the game’s other gameplay leg: Gear combat. Gear combat inflates all the damage numbers to be far more substantial, adding to the sheer power inherent to these larger-scale fights. Additionally, Gear fights are aesthetically different from on-foot battles. Fighting on-foot sees all party members and enemies be represented by pixel-based sprites, whereas every Gear and enemy fought during Gear combat is represented by a 3D model. This, along with crunchier audio design, makes Gear combat feel larger than life and more visceral than anything that the player sees in on-foot combat.

Mechanically, Gear combat throws in the additional rule of fuel consumption into combat, which significantly transforms how the player has to consider utilizing their turns. Do you burn through fuel to get turns more quickly, or do you conserve fuel to be able to heal yourself in an emergency? Fuel consumption adds a fun layer of strategy to Gear combat that separates it from on-foot combat. That said, both combat styles share enough DNA between each other to feel like two halves of a cohesive whole. This is most illustrated by the fact that learned Deathblows from on-foot combat unlocks more Deathblows being available in Gear combat. Prioritizing learning Deathblows and gaining more options in on-foot combat inherently means gaining more options in Gear combat that you’d otherwise be unable to acquire.

As cool as this is, the overall options presented in Gear combat are still inherently limited. The most crucial issue of Gear combat is twofold. Firstly, refueling during combat is insanely inefficient. While there are enemies in certain dungeons that actually assist with helping the player refuel mid-dungeon, running out of fuel during a boss fight is certain death. This, in conjunction with Gears only being able to heal by expending fuel, means that players can’t afford to diversify their pace and strategy. To avoid running out of fuel, players need to heal as little as possible. Such a limitation necessitates an aggressive playstyle where players have to consistently perform Deathblows and maximize damage output per turn. This is really the only viable long-term strategy for Gear combat, severely limiting what players can do with the system.

Secondly, players’ success in Xenogears’ combat is entirely dictated by whether they have the most up-to-date equipment. This scenario isn’t necessarily new to JRPGs. The most typical convention of the JRPG formula is the following: fight monsters to afford to buy stronger weapons that allows the player to fight stronger monsters to gain even more money to buy even stronger weapons, and so on. But as the genre’s progressed, there’s more to take into consideration than just having beefing up your characters’ numbers to take on greater threats. JRPGs like Chrono Trigger and Final Fantasy VII both offer Techs and Materia, respectively, that give players the opportunity to express themselves through a defined playstyle. You can theoretically overcome challenging encounters in Final Fantasy VII through smart implementation of Materia loadouts for your party, and you can use certain party combinations to learn powerful Techs that can help you see greater success in Chrono Trigger. Having better, stronger equipment certainly helps, but it isn’t the be-all-end-all when it comes to determining whether you win or lose a fight.

In Xenogears’ Gear combat, having better, stronger equipment is the be-all-end-all when it comes to determining whether you win or lose a fight. Really. If you don’t upgrade your Gears when new equipment becomes available, you won’t defeat bosses. Upgrading Gears makes such a substantial impact in each Gear’s health, fuel capacity, and power that not upgrading puts each character at a significant disadvantage. Since each boss encounter is designed to be comparable to the power afforded by the most recent Gear equipment available, you simply need to have upgraded to the most recent Gear equipment available to stand a chance.

This effectively railroads players into playing the game a specific way. Unlike its contemporaries, there are very few viable strategies in Xenogears. There aren’t interconnected, smartly crafted RPG systems that open the door for various playstyles and customization. On-foot and Gear combat have a tiny bit of room for player expression via limited accessory slots, but for the most part, there is practically no room to ever test out different strategies in Xenogears’ combat model.

This is Xenogears’ greatest weakness - the primary gameplay, its combat, is severely limited and doesn’t offer the gameplay complexity that other titles were clearly capable of providing at this point in the genre’s life. All of this reinforces the fact that Xenogears isn’t necessarily a game that a person plays for the gameplay. While its turn-based combat and RPG systems are serviceable and get the job done, they aren’t exceptional or even memorable in most instances. Takahashi and the team that would eventually form Monolith Soft would not fully embrace gameplay systems with the same depth and ambition as their storytelling until, I would argue, 2010’s Xenoblade Chronicles.

But maybe that’s okay. If anything, Xenogears’ construction and pacing feels crafted in such a way where it knows that its gameplay is not its greatest strength. The frequent stretches of gameplay that don’t feature any combat are as numerous as they are indicative of a confidence in the storytelling on display. Xenogears understands that its combat and RPG systems are, at best, supplementary to the core essence of the game: its ambitious narrative and world.

Gameplay itself could be considered yet another compromise inherent in Xenogears’ design. Outside of combat, the player will spend most of their gameplay running through towns and dungeons - the latter of which don’t do anything remarkable. Dungeons mostly amount to corridors with the occasional navigational puzzle and treasure chest off the beaten path. Barring some janky platforming and stealth sequences, Xenogears’ dungeons are routinely unremarkable on a mechanical level. Like with its combat and RPG systems, dungeons are merely a vehicle to facilitate narrative moments. Xenogears understand that many aspects of its gameplay don’t possess the same polish, depth, and nuance of its script.

Knowing these limitations, Xenogears caters to its strengths as often as it can. Dungeons, janky and lackluster as they are, never overstay their welcome and frequently employ cutscenes within them to grant narrative momentum to incentivize the player to keep moving forward. This spunky commitment to using its narrative strength to compensate for mediocre gameplay instances is a key component of what injects so much charm into Xenogears. Gameplay-wise, this is far from an essential JRPG. But through understanding and embracing its own identity and its own strengths, Xenogears salvages its overall gameplay cohesion and offers something that is still consistently fun and engaging to play through.

Xenogears arguably has some of the best towns in any JRPG. Not only do they serve as great opportunities for worldbuilding, they impose a level of scale and vastness that help Xenogears’ world feel lived in and far larger than anything else seen in PS1-era JRPGs. // Image: Square Enix

A perfect instance of Xenogears catering to its own strength is its commitment to its rich world. I’ve talked earlier about how Xenogears doesn’t have nearly as many locations in its world map as other Square titles around this time period, but the locations that are featured in Xenogears are among some of the most impressive spectacles to be seen on the original PlayStation. The first town that immediately wowed me was that of Bledavik, the capital of Aveh.

This is the first town in Xenogears whose size is so big that it has the player navigate a zoomed out map of the city to select specific zones of the city that they want to explore. This is something that most of the major cities throughout Xenogears employ, and would even be inherited into Xenosaga. This stylistic choice uses abstraction beautifully - having Fei run throughout this zoomed out expanse of the city to illustrate how vast these cities truly are.

Bledavik is specifically as impressive as it is, though, because of the vivacity inherent within its environments. As the player moves through the city’s market street, the camera will dynamically swoop closer to the ground and give a street-level view of the various vendors populating the street. The quantity of NPCs onscreen, the way the camera moves and is fully controllable, and the audio of indistinct chatter throughout the city streets are all tricks that come together to make Xenogears’ world feel truly lived in. This is an especially remarkable achievement given hardware limitations and just how generally difficult it was to create a lived-in city in a game during this era of game development.

Kakariko Village in Ocarina of Time and the slums of Midgar in Final Fantasy VII are impressively designed video game towns in their own right, but they never feel lived in in the way that Xenogears’ towns do. A large part of that, I feel, comes down to the smart presentation that Xenogears employs throughout its entirety. Xenogears ostensibly has a smaller budget than both games I listed as examples just now, but it makes up for having less resources by being more tactical and stylish with the resources it does have. Featuring dynamic camera movement, plastering areas with unique assets that are never reused elsewhere in the game, and creating an unprecedented level of scale throughout its world makes Xenogears consistently feel more vibrant, ambitious, and, quite frankly, interesting to exist in.

This excellent presentation often extends to the game’s cutscenes and story-driven sequences. From POV shots to interesting pixel-scaling to emulate the look of a zoom-in on a character, to committing to using 3D models to represent the more monolithic presences in Xenogears’ world such as Gears and airborne cities - Xenogears’ presentation is incredibly impressive. Moreover, it serves as an important reminder that you don’t need a massive budget to create visually interesting moments. Xenogears does more with less by framing action in consistently captivating ways - and that goes a long way in enhancing the game’s production value to be far greater than even some of its highest-budget peers.

What helps with this is the game’s overall visual style that stands the test of time. As game development was transitioning into 3D throughout the PlayStation era, different games utilized different strategies with regard to how three-dimensional they wanted to be. Some games, such as Suikoden, stuck to the familiar territory of 2D, sprite-based game design. Other games, like Square’s Brave Fencer Musashi, went entirely 3D at the cost of having an overall low polygon count that arguably looks rough around the edges by today’s standards.

For JRPGs and survival horror games, many developers landed on the strategy of using 3D character models that laid on top of 2D pre-rendered art. Games like Final Fantasy VII and Resident Evil famously use this approach and have distinct visual identities because of it. While this approach allowed developers to create vividly detailed environments, the pre-rendered background style hasn’t visually aged gracefully. Modern releases of games like Final Fantasy VII and VIII really highlight the limitations of leaning too heavily on backgrounds that, when upscaled, heavily clash with the look of the characters that populate the backgrounds.

The least common approach during this transitionary era was that of doing the inverse of the pre-rendered background strategy - having 2D characters populate 3D environments. Only a couple games utilized this look - among them being games like Paper Mario and Grandia. As I touched upon in my Grandia review a couple years ago, I find this style to be the very kind that has aged the most gracefully of all the different experimental art styles that emerged from this era. Xenogears may very well be the best instance of this style, too.

I had instances throughout my playthrough where it was easy to forget that I was playing an original PlayStation game. Xenogears’ visual identity is timeless in a way that very few PlayStation-era games are, and the reason for that largely comes down to how the game masterfully blends the heavily-detailed character sprites with the simplistic but stylized 3D environments and models. The contrast of 2D assets and 3D assets is a beautifully complementary one, making for one of the best-looking games of this area. This style, while rare in its original era, has resurfaced in recent years thanks to the HD-2D art style made popular by 2018’s Octopath Traveler, which solidifies the unique power and visual identity of Xenogears’ art style.

Xenogears impresses with other aspects of its production value. One of the aspects of Xenogears that struck me most was its liberal use of character portraits for dialogue. This practice in itself isn’t uncommon, especially for lower budget games. Other JRPGs from this era such as Suikoden and Chrono Cross used this same approach because it’s an effective way to portray detail on characters in ways that rudimentary sprites or low-poly character models can’t express. Xenogears’ use of character portraits is striking because of just how many there are.

While it’s typical to see character portraits of this type be given to important characters, Xenogears goes out of its way to give character portraits to many, many characters, some of whom have a relatively small presence in the story. We didn’t necessarily need character portraits of characters like Alice, Timothy, Renk, Stratski, and Vanderkaum because they all have incredibly minor roles to play in the game. But the fact that these portraits are there at all helps the player become more connected to these characters.

Character portraits in games are usually used in games to express a means of importance to the player - and I think it’s common for players to internalize this as they play through certain games. I can tell when I meet a character I can recruit in Suikoden II because they have a character portrait. The presence of a portrait implies an importance to that character that subtextually informs me as the player to pay attention to this character as a possible recruit instead of another character that lacks a character portrait. The level of detail implies importance to the game’s mechanics and systems in this context.

Because Xenogears is willing to give character portraits to so many characters, it’s easier to view many characters as being an essential part of its story and world. in the moment. It’s easier to get invested in even minor characters in the game’s plot because the presence of portraits in other games has unconsciously convinced that such a thing makes a character more significant and worthy of our attention. This works in Xenogears’ favor, as I think most players will think that there will be more to a character like Alice since she has a portrait. Since the developers went out of the way to give her a detailed portrait, we, as players, become convinced that she’ll have a greater presence in the game to justify the time and detail that went into her character portrait. But this expectation becomes shattered when Alice’s role in Xenogears gets cut short incredibly early into the adventure.

The presence of character portraits is even used as a way to communicate narrative information. While the party is in Shevat, we learn that Maria’s father, Nikolai, has been kidnapped and is working for Solaris. This culminates in a boss fight where the revered scientist has become brainwashed by Solaris and attacks the city, against his own daughter. As Maria talks to him, there’s a piece of her father still underneath this brainwashed, hate-filled husk of a man. Amidst various dialogue we hear from Nikolai during this encounter, we eventually hear Nikolai plead for Maria to defeat him.

What seals this narrative moment is that the only thing that implies to the audience that this is the voice of the real, pre-brainwashed Nikolai breaking through the noise is that it’s only during this moment that we see Nikolai’s portrait. The presence of a portrait - one that shows a seemingly normal-looking father that doesn’t appear nefarious or cruelhearted - communicates to the audience that this is the real Nikolai that we’re hearing from, if only for a moment. It’s a smart moment that utilizes the unique aspects of Xenogears’ visual language in a creative way.

Such a moment is special because it’s emblematic of what makes Xenogears so special. It’s a seemingly small detail born out of limitations requiring the game’s developers to be creative with how they communicate information to the player. Xenogears is a game brimming with details that most games of a similar or higher budget would have forgone in the interest of developing the game more efficiently. But to Xenogears, the detail and depth inherent to every part of its design is essential to the overall experience.

The world, story, characters, and design of Xenogears try to accomplish so much with decisively limited hardware and development resources. For the most part, the game pulls it off. Sure, there’s compromise that can easily be seen in aspects of the game’s presentation and the hyper-linearity of the game’s combat progression and overall structure, but the game primarily succeeds at what it sets out to accomplish.

I’ll gladly take combat that feels limited compared to other JRPGs if it means that I get to see the ambitious depiction of the flying city of Shevat - a visual showcase that looks unlike anything else on the PlayStation. I’ll gladly accept going on a mostly linear adventure if it means that I get to witness some of the most shocking and smartly foreshadowed plot revelations in any JRPG. There are compromises and weaknesses inherent to a lot of different parts of Xenogears’ design, but I think such compromises were the right ones to make in the context of making as good of a game as possible out of an imperfect situation. If Xenogears couldn’t have a larger budget or more time for its development, than I think the specific cuts in content that Xenogears makes were the right compromises to make in order to get the game out the door.

In another time and in another situation, Xenogears could have been a lot more than what it is. It could have achieved more than what the final product we got could. Even though we won’t ever get to see what Xenogears could have been in such a circumstance, the Xenogears that we know today gets more impressive the more familiar you become with the context in which it was developed. Because Xenogears couldn’t be the perfect game that it was perhaps envisioned as, compromises were made as Takahashi’s team sought to make the best game that they could with the situation they were given. And that is precisely what makes so many of Xenogears’ ambitious decisions feel so heartful and charming. The various decisions around different parts of Xenogears’ design - from its combat to its art direction to its presentation style - do their best in spite of the compromised circumstances that threatened their potential.

The game’s excellent soundtrack is even a product of compromise and hardship. Yasunori Mitsuda, the composer of the game’s soundtrack, collapsed from exhaustion while working on the game’s soundtrack. In spite of an unhealthy work ethic, much of the world and storytelling within Xenogears gets so much additional texture because of the bizarre, otherworldly, and often somber tone of the game’s soundtrack.

Of course, the secret weapon within Xenogears’ arsenal is its phenomenal story that feels unlike anything in the industry. Xenogears’ story is thought-provoking, intellectual, profound, and completely reframes what video game storytelling is capable of. Despite the strengths of its narrative, Xenogears also sees compromises in its story, with party members’ backstories getting the short end of the narrative stick and the game’s second disc abridging a lot of major events. Xenogears is ultimately more interested in the high-concept ideas of its story, especially as they relate to Fei and Elly, the two characters that get the most attention throughout Xenogears. This prioritization ultimately causes characters like Rico, Billy, and Maria to get thrown to the wayside with storylines that feel rushed and incomplete.

I’d be remiss to act as though Xenogears does no wrong with its narrative. There are clearly shortcomings present even in the strongest aspect of the game, but that isn’t enough to drag down what is an exceptional narrative that begets further discussion.

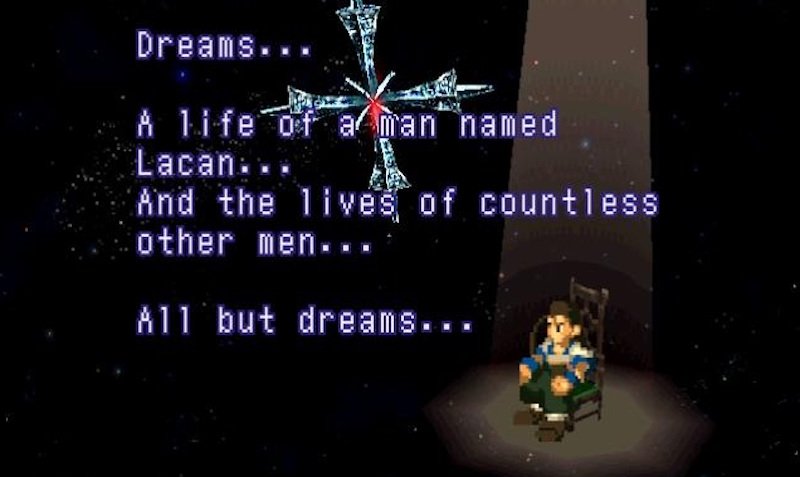

The shot of Fei sitting in a chair under a spotlight with stars in the background as text crawls onto the screen is perhaps the most iconic visual aspect of Xenogears. Despite its abandonment at balancing the story and gameplay volume to be on comparable levels, Xenogears’ second disc offers many of the game’s best moments thanks to inventive, revelatory writing and direction. // Image: Square Enix

The remainder of this blog post discusses heavy spoilers for Xenogears, Xenoblade Chronicles 3, and Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Upon looking at any fan conversation about Xenogears in video essays, forums, or social media, it won’t take long to see that Xenogears gets directly compared to a few key pieces of media. While in Solaris, Fei and Elly consume some of the food that’s distributed from Solaris’ government throughout Solaris and the land-dwellers that live on the planet. Immediately after, they learn that this processed food is Soylent - food made out of people. What’s more, this food is processed to instill Limiters into people - effectively serving as a form of population control among the masses to serve the interests of Solaris’ founders.

This thread is reminiscent of the 1973 dystopic thriller, Soylent Green, a film that bears a similar plot thread. Another striking similarity that Xenogears has with another piece of media is that of Kubrick’s masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey. That film opens with the Dawn of Man, a sequence featuring apes who discover a monolith that intrinsically changes the course of human history from that point on. Likewise, in Xenogears, the Zohar, a similarly shaped monolith featuring limitless power, changes the course of human history and powers boundless weapons such as Deus well into humanity’s future.

One of the most common comparisons that Xenogears has with other media, and the one I find the most compelling, is that of Neon Genesis Evangelion. This influential anime and Xenogears get compared to each other a lot for their supposed similarities with regard to their aesthetics, thematic content and density, and overall direction. Like Xenogears, Evangelion starts out as a typical iteration of its respective genre with a good measure of intrigue and mystery sewn into the narrative. The first half of Neon Genesis Evangelion is a mecha anime that regularly features fun action, intriguing character drama, and an overall tone that feels familiar to other mecha works.

But about halfway through Evangelion’s run, the show’s tone and focus significantly shift. What was once an entertaining continuation of the familiar becomes something more twisted and intriguing. Evangelion has become as iconic as it is because it’s a critique and subversion of its own genre, and pivots to asking more existential questions that naturally arise out of the conflict depicted in the anime. The intellectual yet dreadful existentialism of Evangelion doesn’t get introduced until the series is in its second half, and it gradually culminates in taking over the entire show. Not only has this subversion ultimately defined Evangelion’s legacy, but it has cemented it as an example of how aspects of genre fiction can be utilized as a framework to ask far broader, more existential questions.

The last two episodes of Evangelion are specifically noteworthy in that they allow the show’s abstract existentialism to take hold of the entire narrative, with much of what’s depicted in those last two episodes being largely open to interpretation. In the thirty years since, there’s been much speculation over why this is the case. Some feel that the final act of the show was born out of a lack of budget and resources. Maybe the end of the show was the way that it was because a more conventional conclusion hadn’t been written or couldn’t be produced within the show’s allotted budget.

Occam’s razor ends up being the case in this instance. The anime went in this direction because Hideaki Anno’s mental health at the time of production naturally led him down the path of making Evangelion’s second half in the way that he did.

The conversations around the similarities between Evangelion and Xenogears tend to function around the hard pivot that both stories make around their halfway point. In the case of Xenogears, the game’s second disc marks a clear departure from the first disc, which constituted a more conventional JRPG experience. The first disc of Xenogears regularly features cutscenes, combat, dungeons, towns, and a world map that all interlink with one another to create a conventional and functional JRPG experience. But once the second disc begins, that familiar structure evaporates and becomes something far different.

Xenogears effectively becomes a Spark Notes version of itself throughout the second disc, taking entire arcs that would have taken hours of gameplay and condensing them into a few paragraphs of narration by Fei or Elly. The cutscenes that once regularly constituted story progression are now primarily framed by the now-iconic depiction of Fei or Elly sitting on a chair under a spotlight with a dangling Pendant of Nisan swinging above them. On top of this, some of the game’s most thematically dense and existential revelations happen during this part of the game. In nearly every aspect, Xenogears’ second disc is a departure from what precedes it, and that’s what makes it stick with the audience so heavily. The tonal and stylistic shift in the second half of Xenogears is a defining aspect of its legacy, not unlike Evangelion’s iteration of this concept.

The key difference between Xenogears and Evangelion in this context, though, is that Xenogears’ structural and tonal shift truly was born out of a lack of resources and time. Squaresoft originally advised for Takahashi’s team to end the game at Solaris - the end point of Disc 1. Knowing that ending the game at that point would leave audiences on a massive, dissatisfying cliffhanger, Takahashi instead opted to create a collage of sequences that expedited the pace of the adventure in order to deliver a satisfying conclusion at the expense of gameplay cohesion. Story-driven cutscenes take up the vast majority of Disc 2 to the point where Xenogears effectively becomes a visual novel with boss battles and occasional dungeons to explore.

From an objective standpoint, there is a jarring inequality between the two discs. Xenogears’ first disc is a JRPG that regularly combines story and gameplay sequences to create a story that comfortably fits in a familiar video game structure. Once the second disc begins, though, the way in which Xenogears tells its story is significantly compromised. There is no longer room to become immersed in the game’s world as narrative information simply gets told to you. Many plot reveals, such as Khan Wong being both Wiseman and having merged with Khan, have to just be accepted by the player because the game simply doesn’t have enough time to properly develop and build up to this reveal with the meticulousness and tact that the game would have been capable of with the structure of Disc 1.

Many narrative moments end up feeling rushed because they are. Xenogears features a mammoth amount of story in its second half - to the point where it can be argued that more things happen in Disc 2 than in Disc 1 despite its significantly shorter length. That leads to Disc 2 feeling a lot more compact and deep with regard to its narrative and plot reveals, and it can be truthfully overwhelming. Not only is there a lot of story that happens in Disc 2, but story takes up the vast majority of content in Disc 2, meaning that most of the player’s time throughout the second half of the game will be absorbing the swathes of information presented by the game.

There’s a part of me that acknowledges that the jarring rift between the presentation of content between Xenogears’ two discs should be criticized as something that holds the game back. There’s a part of me that wants to say that this compromise is so significant that it limits the potential of the game’s overall storytelling. It’s easy to wish that a modern version or remake of Xenogears could fully realize the game’s intended scope and narrative by making Disc 2’s sections entirely playable and consistent with the presentation of Disc 1’s contents. But this compromised abstraction of Xenogears’ storytelling throughout Disc 2 is an essential aspect of Xenogears’ overall legacy and impact that it leaves on everyone that plays it.

There is a lot that the player needs to read and understand throughout Disc 2 - so much so that I’m uncomfortable giving a full, in-depth analysis of the game’s events, themes, and greater meaning until I complete additional playthroughs. But the most essential part of it is that it provides well-thought-out context that significantly reframes all of the events that take place throughout the game. The presentation of information may be compromised in many ways, but the actual content of the narrative doesn’t feel toned down in any significant way.

Most crucially, Xenogears’ style during its second disc is unlike any other game that has released before or after Xenogears. The compromised storytelling ends up becoming a style that is, in itself, impossible to forget. The creative approach that Takahashi’s team went about telling the second half of Xenogears’ story ends up becoming the defining characteristic of the game that will likely stick with players long after they put the controller down. I will never forget Xenogears nor its story because the creative ways in which the game overcomes its developmental limitations, while ostensibly compromised bastardizations of the game’s original creative vision, become themselves an integral part of the game’s identity. Compromise becomes part of the game’s charm because the compromise needed to exist in the way that it does in order for the game to reach a shippable state in the first place.

I find immense beauty and inspiration in that. Xenogears couldn’t have been the game it was originally envisioned as, and yet the compromises that the development needed to make to get the game out the door perhaps turned Xenogears into the game it needed to be. The game doesn’t let its compromises and limitations get in the way of the ambitious story that it aims to tell.

This is to say nothing of the overall quality of Xenogears’ final narrative. There are some clear issues with the game’s narrative that I’ve outlined already - and the clearest weakness of Disc 2, beyond how some plot threads are rushed through, is the fact that character development largely gets left behind. Characters no longer get moments in the sun where we can see more of their development. Disc 2 largely focuses on the core narrative as it relates to Fei, Elly, Krelian, Miang, the Zohar, Deus, the Wave Existence, and the cyclical nature of the conflict enveloping the world of Xenogears. It’s a shame that some characters get thrown to the wayside for the sake of the broader narrative, but what softens the blow is that the broader narrative is damn good.

Among the many aspects of Xenogears’ narrative that I found uniquely compelling, I find the most intrigue with the connection between Fei and Elly. Fei, the latest reincarnation of Abel, the Contact between mortal life and the Zohar, created the original Elly, a female figure born out of Abel’s desire for motherly love. Over the following centuries, Fei and Elly would be reincarnated under different names but always intersect in one another’s lives. While the love between them in each incarnation would naturally fester, tragedy would ultimately split them apart. Fei and Elly’s love for one another transcends individual incarnations, which makes their connection all the more tragic, and their desire to end the cycle that has brought such tragedy into their many lives become a more compelling plot thread to see to its conclusion.

This particular aspect of Xenogears is one that would be revisited by Monolith Soft’s works - namely in the form of Noah and Mio’s relationship in Xenoblade Chronicles 3. While the circumstances regarding Noah and Mio’s various incarnations is in an entirely different context compared to Xenogears, the tragedy between Noah and Mio’s fated union and separation creates equally compelling drama.

Beyond the game itself, Xenogears leaves an intriguing and charming legacy because some of its ideas have been revisited by its own creators, and the fact that such ideas are revisited in such different contexts in future games gives merit to the broadness of these ideas. Like 2001’s idea of a monolith redirecting the course of human history, Xenogears posits various ideas that are so broad and ripe for different explorations that it gives creators myriad ways to find inspiration. If even its own creators can revisit certain plot ideas and explore them in different ways, why should any creative soul not look to the ambitious ideas of niche video games as inspiration to be bold and ask complicated, human questions?

There is a lot to unpack with Xenogears’ narrative as both a consumer and as a creative. As a video game player, I’ve made the effort to understand its story as best I can by reading supplementary material, reading fanmade analyses, and reading developer interviews to understand the intent behind the game’s ideas. As a consumer, I’ve become fully invested in Xenogears’ world and mythos. As a creative, this clear ambition and heart behind the many ideas expressed within Xenogears’ narrative has inspired me to work towards making my own mythos that can inspire future generations.

My genuine hope is to make a piece of art that immerses someone and puts someone in an intellectual chokehold in the way that Xenogears has done to me, because I can attest that such a thing is previous. It’s special when a game makes you ask questions about the world, about reality, about life, about the very essence of being and have a great time while you’re doing it. My creative ambition is to create a world and story that can do such a thing to someone in the future. The most emboldening part of this is that Xenogears has managed to make me become so engrossed and intrigued by its story, world, and characters despite, and in some ways, because of its compromised state. Even though the game is inherently flawed, compromised, and arguably incomplete, it still has managed to positively impact my life and encouraged me to think about the world and storytelling differently.

Xenogears’ imperfections not only work to its benefit, it reminds us that you can make something that changes peoples’ lives even if it’s flawed, even if it’s incomplete or imperfect. If Takahashi and his team could somehow get Xenogears in a shipped state and create a compromised but playable depiction of Takahashi’s original vision, then why can’t you do whatever you can to finish that book, album, movie, or game you’ve been working on? Maybe it won’t be the exact vision that you have in your head right now, but it will be a finished product that someone can buy, spend time with, and enjoy. Maybe if you’re lucky, that person will even write a blog post about it in thirty years or so, talking about how your book’s ambitious nature positively affected them even though it wasn’t perfect.

Xenogears is as beautiful as it is because it is a reminder that compromise doesn’t rule out the ambition and heart that we can put into our creative output. We are all capable of making incredible art that seeks to take the ideas and worlds we’ve crafted in our head and convert them into tangible relics that other people can engage with and try to understand. Maybe nothing we make can entirely translate the thought wavelengths in our head directly onto the page, but the willingness to try our best to make our intangible thoughts digestible to others is what artistry is and should always be about.

In Xenosaga -Official Design Materials-, Takahashi discusses how video games are inherently an inefficient medium for storytelling. “With games as a form of media, no matter where you set it you have to make towns and all the little accessories. With movies, for example, if it's based in present times you can just shoot on location. You end up doing annoying work with games. That's why I don't think it's a good medium for telling stories. I think it's better to call it a media for telling narrative things. Without a doubt, there are things you can't get across in a game.”

I’m inclined to agree with Takahashi - there are a lot of obstacles that get in the way of video game storytelling that make the medium more difficult to tell stories in compared to that of other forms of media. In spite of that, though, fantastic, inspiring stories are still capable of being told. In that sense, it can be argued that every story told in a video game is compromised. From Cyberpunk 2077 to Final Fantasy VII Remake; from NieR: Automata to The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, every video game story is perhaps unable to communicate all of its originally intended narrative ideas because a lot of the “annoying work” in games inevitably takes attention and resources away from time that could be spent on crafting as great a narrative as possible.

Ultimately, video games, movies, books - all media are products that have to release. By their very nature, shipped products have limitations of time and money that ultimately restrict their potential. There is no such thing as a truly “uncompromised” vision - especially in video game development where collaboration is an essential bedrock of the entire industry.

The question is never whether your creative vision will be compromised. Rather, the question is, how will you take advantage of the compromises and sacrifices you must make and the limitations that you have to work with to creatively achieve your vision as closely as possible? In the case of Xenogears, I truly think Takahashi’s team asked themselves that and landed on a final state that makes it one of the most special games ever made.

Xenogears is jarring, it’s bizarre, it features uneven pacing, much of its gameplay is average and doesn’t surpass the heights of its contemporaries. Xenogears is a game that may be flawed, but each of its flaws are tangible sacrifices that were made in service of making the game and its heartful, ambitious ideas reach the hands of players. Xenogears isn’t perfect because there isn’t a universe where it could have been, and that’s what makes the game special - it features an undying willingness to convey its mind-bending ideas even if limitations of its existence as a video game with budget and resource ceilings get in the way. In spite of the obstacles in its path, Xenogears carves its own path and tells an incredible story in an incredibly creative, stylish way born out of limitation and compromise.

Xenogears could never be developed with the intention of being charming, and yet it ends up being just that. Xenogears achieves the elusiveness of being a game filled with charm because it aims to be something that will stick with people in spite of the odds that were placed against it. Charm gives way to inspiration towards its audience. The charm and inspiration that Xenogears leaves on its audience naturally invite and encourage everyone that plays it to try sharing their own creative vision with the world. We had to compromise to make this game a reality, so why can’t you do the same? the game practically asks.

I think we should take heed of that question. Xenogears proves to us all that compromise is not a scary word. It’s something that we should embrace and allow us to get creative with how we tell our stories and present our ideas to the world. So let’s do just that.

If Xenogears leaves any precedent, it’s that we can at least count on whatever we end up making to become something that matters to someone. Maybe, just maybe, what we make can also become infectiously charming to those people in the process.

Thank you very much for reading! What are your thoughts on Xenogears? What other media do you think is compromised but still special? As always, join the conversation and let me know what you think in the comments or on Bluesky @DerekExMachina.com.